BOOK REVIEWS

PARADISE LOGIC

by Sophie Kemp

About

Genre - Contemporary, satire

Reviewed - October 22, 2025

Rating - 4.5 stars

Synopsis

The quest undertaken by one 23-year-old Reality Kahn as she strives to find a boyfriend and, once she finds him, become the best girlfriend of all time. It was decreed from the moment she was bornth.

My review

* This review contains sexual content.

Reading "Paradise Logic" feels like getting your brain fried in battery acid, or maybe getting zapped by hot pink lightning. Don't click off just yet.

The millennial novel is a strange beast and not one that many people have been able to conquer. Go into any bookstore and its shelves will be lined with an endless conga line of self-absorbed commentary on the Contemporary Plight, complete with gratuitous reference to the 'net, and they all fail to say anything interesting interestingly.

Not so with "Paradise Logic". This isn't a novel about the internet as much as it is one born of it, presenting a truly bizarre smorgasbord of 'current' issues which it then proceeds to hack to pieces in its lucid, absurd conclusion. I am *so sick* of books about the internet, and it was refreshing to see one not overmuch concerned with it. The internet is present in "Paradise Logic" because it would be impossible to write a story set in twenty-first century New Yawk without it, but it's an encompassing force. No need to address it directly or moralize, obliquely or not—it's already permeated everything.

And her skin was so firm. And the clusters of acne on her chin were kind of cute. And her hands were so strong. And she didn't look weathered. And when she smoked a cigarette it didn't make her chest hurt. And if she were to have seven vodka with eggs at a bar with cracked vinyl booths it would not hurt her head the next day. And if she were to kiss someone she did not need to know if they were a genuine eighties baby or if they had a parrot named McSamson Domingo at home. And the main thing that she did was make what she thought was art but were actually just little magazines that she did on her computer about the major issues of our time featuring drawings and collages.

What is it about? It is about a girl. It is about a girl and her name is Reality and it was decreed when she was bornth. It is about a girl named Reality on a quest, and this quest is to first obtain a boyfriend and then to become the bestest girlfriend ever. It is a dizzying tour-de-force of satire, cherry-picking elements of the manic pixie dream girl, the sexy bimbo, and the Jakey worshipper in an oddly tragic picaresque. Reality talks like a lunatic, has a "low quantitative IQ", and is endlessly endearing as far as erstwhile protagonists go, and her trippy descent into the world of psychopharmaceutical alchemist Dr. Zweig Altmann is one that creeps up on you even though you're staring it in the face the entire time. It's a book that wants to make you uncomfortable and it certainly will, but more than that, it wants to show you the deep-seated aches that come with youth and power and sex and love and gender and have you laugh at them because they're ridiculous and stupid and they hurt so bad and they're so scary.

Ariel was very athletic in the art of the sexual, and I was seriously amazing at knob slobbing. It was a real gift. And I was so lucky to have this because a girlfriend must be able to suck cock. I had learned it from a man who we will call the European; me and the European met while I was summering in the Slovakian countryside and was in some need of jam and cheese from the local market and he, too, had the same objective. It was a summer romance. Goldenrods, thyme, Cinzano in a pale green cup with a single ice cube. A paisley couch on a back porch. It was every day, mostly in the afternoon, that he sat me down and said: "Please, no teeth! You are making it hurt very badly." And I learned, oh how I learned. I went up and down. I whispered to the shaft so it would do what I pleased. The European would convulse and I would feel him begin to drip inside of my mouth and the foreign sentences he uttered were those of immense pleasure.

And then it was the 11:30 a.m. plane out of Bratislava. And then the present transitioned to memory and the European became a dream on my cell phone. I still heard from him. It was quarterly. He would often send me a website link to a video of a svelte Cuban man singing the songs not of love but of pure, carnal ecstasy. And I would always respond: "Thank you, the European!" This was one of my best sexual memories.

Things *happen* in this book. Things are *thrown* at you. Seriously crazy things. And, naturally, there's no time to digest any of it. Sentences will start one place and happily skip into an entirely unpredictable secondary, tertiary, quaternary location, caked in so many labyrinthine layers of irony that you start losing your head a little. Sophie Kemp knows how to do witty turns of phrase and is a connoisseur of word choice. The end result are slick paragraphs that you read veryvery fast, hence the brain-frying or the lightning-zapping. It's the very best kind of satire, and it is wildly funny and wildly sad, the latter because of the moments where the onslaught lets up momentarily and you see the heart of the matter, a heart I'll leave to you to discover on your own read. The landscape it presents is a bleak one, but the thing is, it's a familiar landscape and Kemp examines it precisely. The conclusion, when it comes, is deeply underwhelming in a way that completely fits.

A TV was switched on, and on it they were advertising an amazing new type of medicine that if you are a man and sometimes it is hard for you to perform sexually inside of a woman's organ, you can get some assistance. I was very transfixed. A man was climbing a mountain with a beautiful lady, taking in the vistas.

"Thanks to Adonis-XR, me and my wife, Rebecca, can climb the Matterhorn every night!" he said.

Then the name of the drug flashed on the screen in a beautiful cursive font, alongside the name of Dr. Zweig Altmann and some facts about how a possible side effect was that you might want to kill yourself.

This did not seem like medicine that Ariel needed. He was always ready to go in sexual matters. This was one of the many things that I enjoyed about Ariel. He was a real go-getter. He had a zest for life. He was always saying stuff like "I want to cream inside of you" and "Take your fingers and put them in your pussy and tell me how wet I make you." Me and Ariel, we loved intellectual conversations such as these ones. I was so lucky that I had such a special guy to chitchat with all the time.

I can't in good conscience recommend "Paradise Logic" to anyone. It's weird in the literal sense and deals with weird and grim topics with typical conviviality. If any of that sounds like something you'd like, I think you should maybe check it out. I really enjoyed it. It's a fun read and an overall fantastic time, but it's the kind of thing you have to be in the mood for.

THE SUMMER TREE

by Guy Gavriel Kay

About

Genre - Fantasy

Series - The Fionavar Tapestry, #1

Reviewed - September 20, 2025

Rating - ?!?!?!?! I DON'T KNOW

Synopsis

Five university students - Paul, Kevin, Kimberly, Jennifer, and Dave - are spirited into the magical world of Fionavar to attend a festival in its High Kingdom. Soon enough, however, the friends find themselves caught up in an ancient conflict between the forces of good and evil, and are forced to join forces with a whole host of warriors, elves, dwarves, and mages in an effort to fight against the Unraveller.

My review

* This review contains discussions of rape (and spoilers). Skip the paragraph marked with an asterisk to avoid the former.

I genuinely, *genuinely* don't know how I feel about this book, but I suppose the whole point of this review is to parse that out. First things first: I don't mind that this book is derivative of Tolkien's Middle Earth novels! It was initially published in the 80s and you'd be hard-pressed to find *any* fantasy novel from the 80s that wasn't at least a *little* based on "The Lord of the Rings". I wanted to address that first because a lot of the negative reviews I've seen so far bring that fact up. I think it's less a failing on Kay's part and more an indication of just how profound Tolkien's impact on the genre was.

So now that that's out of the way, what'd I like about this book?

I thought it was gorgeously written, for starters. The beginning was choppy and it's clear Kay was still finding his footing in Fionavar as it was being written, but he quickly made up for it. Kay's writing is melodic and uses repetition masterfully. I was reminded of how *I* write at a lot of points, or would like to write; he's interested in emotions and how they translate into prose, and I really appreciated that, and he did well by it.

Building off that, Kay's character-work is great. A lot of people are introduced in a relatively short amount of pages (the novel is only about 300 pages long), but they all have distinct personalities and motivations (save for a particular group I will touch on later). It was very easy to care about them. They're all very archetypical - Loren is the wise mage, for example, and Matt is the gruff and loyal dwarf. Diarmuid is a prince who loves wine and women but is also sharp and cunning; Ailell is the once-noble king; Rakoth Maugrim is evil incarnate. They all embody clear niches in the genre and I suppose that also made it easier to care about them because it was so obvious how I was meant to feel.

The third important point in a fantasy novel: The worldbuilding was good! Fionavar is a charming place and it has distinct cultures and areas, even if most of them were underdeveloped save for Brennin (in this book, at least. That might (and should!) change in the coming installments). There are a lot of interesting threads dropped into the mix (see what I did there?), such as the delightful titular Summer Tree. I loved the originality of the idea and the gravity of its execution, and I loved Paul's character arc in relation to it. That kind of thing is exactly what I like to see in fantasy. I'm being intentionally vague about what happens because that's not what I intend to spoil.

Overall, "The Summer Tree" had all the elements of a fantasy book *I* would love and most other people would at the very least enjoy. It has solid characters, intriguing worldbuilding, and good writing. So then, what's the problem?

There are kinds of action, for good or ill, that lie so far outside the boundaries of normal behavior that they force us, in acknowledging that they have occurred, to restructure our own understanding of reality. We have to make room for them.

The problem is, of course, that Guy Gavriel Kay is a man and this book was written in the 80s. Remember earlier how I mentioned there's a group of characters written worse than the rest? Yeah. It's all the female characters. Actually, strike that thing about the 80s; a lot of books were written in the 80s which weren't totally horrible to their female cast of characters. But before we get into that, a note on the pacing.

The pacing in this book was *wild*. There would be pages and pages of excellent plot and character interactions, and then that would be interrupted by something deeply boring and uninteresting. What comes to mind is a truly dull portion of the book in which Jennifer watches a group of children playing a weird magical game. I wouldn't mind that sort of thing if it didn't happen so frequently.

Back to the issue at hand. There are two FMCs in this novel - Kim and Jennifer. There's a scattering of supporting female characters: Ysanne, an old seer; Jaelle, a priestess; Sharra, a princess. I want to touch on all of them here.

Each individual male character in this book was afforded more care and attention than all the women put together. There's a line in which a character tells another that he knows how to talk to men but not to women, and that, to me, was really emblematic of Kay's entire attitude towards women. Men are characters and people and they're allowed to occupy space and have relationships to each other that are deep and meaningful. They're allowed to fight, to have adventures, to learn things. Women are not people, so they aren't allowed to do any of that. The best example of this is Kim.

Kim is the FMC we spend the most amount of time with, if you count her dozen or so POV pages as being a significant amount of time. Kim is a seer who leaves her friends shortly after coming to Fionavar in order to spend time with Ysanne, a much older seer. In her time with Ysanne, Kim discovers her own powers and learns the entire history of Fionavar - yet so little attention is paid to this! Kim goes from ordinary girl to seer and yet her role in the story is only to act as a vessel for the lore and to warn other characters of danger. She's hardly a character; Kay thinks that a few sentences showing her bonding in exposition with Sharra and being told of her friendship to Jennifer is enough to establish her as a character with meaningful relationships to other characters. The most emotion I see from her is her (admittedly moving) words directed towards Jennifer in the final pages of the novel and her conversations with Aileron; though, because Aileron is a man, the brunt of the focus shifts onto him whenever he's present.

I've mentioned Jennifer a few times now. She's definitely the character treated the most horribly out of my list, but Jennifer is hardly in the novel. While Paul and Kevin are off having adventures with Prince Diarmuid and Kim is learning magic with Ysanne, Jen is left to while her time in the castle. She does this by sitting with the ladies of the court, a vapid and status-obsessed group of young women, the leader of whom is little more than a high school bully. Jen goes out with a 'friend' (we hardly get to know her) and meets Jaelle, who I'll get to later. After this, she meets the lios alfar (Fionavar's version of elves) and parties with them until the group is attacked by the forces of darkness. Jen is kidnapped and taken to Rakoth Maugrim, the Unraveller. We don't hear from her again until the ending of the book.

* The ending of the book is when I truly understood how little Kay sees his female characters as valuable characters because this is when Jennifer is raped by Maugrim. The rape is awful, and Kay lingers on all the wrong parts of it - the Unraveller takes the form of important people in Jen's life and assaults her in their guise. Jen, throughout, is brave and noble. This is merely a thing happening to her - Kay is uninterested in how severely sexual violence differs from any other form of torture. Furthermore, of course he chooses rape as Jennifer's punishment because she's a girl, and what else could he possibly do? "Why rape?" is never questioned. It's not that it's unnecessary because I do believe sexual assault has a place even in works that aren't *about* sexual assault, but I believe that it deserves gravity and respect of a sort that Kay did not afford it.

Of the supporting cast, Ysanne's problems are similar to Kim's, and I wouldn't mind - she's the most fairly-treated of the roster - if it weren't for the fact that no other female characters were written well. Sharra is treated as an exotic conquest - we meet her when Diarmuid has sex with her under false pretenses, and we are still meant to like him after this. Later on, she attempts to assassinate him and fails, but is won over somewhat when he pardons her and makes a roundabout and veiled apology for slighting her honour. Jaelle is cruel and catty and ambitious, which women are not allowed to be. She is deeply unlikeable and deeply stereotypical in a way that feels different from the archetypical nature of most of the characters.

I also want to give a cursory overview of the diversity of Kay's cast of characters. It is, expectedly, a bleak situation; most characters are at some point or the other described as being fair-skinned, and an entire culture is blatantly modelled after some vague idea of Indigenous Americans.

I think "The Summer Tree" was, if you exclude the women, pretty good. It was an enjoyable read and I found it to be a solid work of fantasy. Many fans of Kay's writing say that it's his weakest work (I believe Kay's roundhouse is historical or historically-inspired fantasy), but I thought it was good regardless. Once you factor in the female characters, though, this book takes a heavy blow. I can't excuse its treatment of them for the time period, and it's really obvious that Kay doesn't see them as real people the way he sees his male characters as real people. At one point in this, a father literally tells his daughter to go help her mother in the kitchen because the grown-ups are talking. Women, in "The Summer Tree", are sexual conquests - Sharra, Jennifer - or plot devices - Kim, Jaelle. They are embodiments of the dead wife - Paul's dead girlfriend. They are fodder. They are not real people. I can't forgive that, and that's why I'm so torn on how I feel about this novel. I wish it were better. That's all I can really say!

THE HAUNTED WOOD: A HISTORY OF CHILDHOOD READING

by Sam Leith

About

Genre - Nonfiction, history

Reviewed - September 20, 2025

Rating - 3 stars

Synopsis

A history of children's books that touches on all the genre's landmark works, from the beginning to the present day.

My review

I picked this book up from the 'new acquisitions' section of the library because of the gorgeous cover art and, of course, the Lemony Snicket endorsement on the front cover. (Snicket himself is only mentioned in passing.) Conceptually, this book is fantastic - and it *was* really good, for the most part. Leith truly understands what exactly it is that makes children's literature tick and why it's so appreciated and cherished today, even if this wasn't always the case. His writing is engaging and light while still conveying a great deal of information. The survey he presents is thorough.

That's why a surprising constant in a literature associated with ideas of freedom and innocence is grief. Many of the most enduring and most moving of these stories have a pulse of sadness in them or behind them. To be a child is to know that you have to grow up. To be an adult is to know that you have to die.

You might be thinking, but if you enjoyed it, then why did you rate this 3 stars? And I do have an answer for that. You see, any history book will eventually have to contend with bigotry, especially if it's a general survey like this book is. Leith is diligent about pointing out the biases that authors like, for example, Roald Dahl held - he devotes pages to Lewis Carroll's potential pedophilia. That's why it's curious that when he finally reaches a living author whose bigotry is making the lives of many, many people markedly worse, he devotes a shoddy paragraph towards 'cancel culture' and nothing more. This author is, of course, J. K. Rowling, and Leith's bias towards his appreciation of her books clouded his writing of her longer-than-necessary chapter. Compounded with a few other eyebrow-raising moments in this, I felt I couldn't in good conscience rate this any higher, and I stand by that.

Also, and I know this is less the author's fault, there were a *lot* typos in this book, particularly in the first and last quarters; these ranged from paragraph breaks occurring mid-sentence to, bizarrely the fact that most proper nouns staring with the letter 'v' were in lowercase (?). I found it hard to move past them mentally given their number and how distracting they were.

Overall, this book could have been much better if it weren't clouded by Leith's bias. I understand Rowling's work is important to the landscape of children's literature, but I don't find that excuses her harsh and blatant bigotry and hate-speech. She, unlike Dahl and Carroll, is still alive and actively making the world a worse place.

A TOUCH OF JEN

by Beth Morgan

About

Genre - Contemporary, millennial social satire

Reviewed - May 20, 2025

My rating - 4 stars for the first three quarters and 3 for the last quarter.

Synopsis

Remy and Alicia are a couple of insecure, unremarkable twenty-somethings who live in a cramped apartment with their perennially-cheerful roommate, Jake. When not at their serving jobs, they spend their time obsessively looking through the Instagram page of an influencer Remy used to work with — Jen. A chance encounter with Jen leaves the pair with an invitation to join her and her friends on a surf trip to the Hamptons, an invitation which opens the door to cosmic strangeness galore.

My review

Alicia says that maybe she should print out a photo of Jen's face and tape it over her own while they have sex. "I could cut little holes in the eyes."

I picked this one up because it was available at the library and bore a review by Carmen Maria Machado, and I'm glad I did because I was really pleasantly surprised! I honestly didn't think I would like it at first, and you will think this is a silly reason for why, but it's because there were emojis in the inside cover text. The story itself juggles the topics of authenticity and inauthenticity really well — the whole thing feels a bit like you're looking at the world through an 0.5 camera lense; everything's a bit warped and buggy-looking. It's funny, and hits a good spot for social satire since it's not cloying while still obviously exaggerating its satirical target. I find that's a difficult balance to strike. The movie "Bodies Bodies Bodies", which I remember being pretty well-received and is the closest analogue that I can think of right now, felt a bit exhausting at times, but this book maintains itself quite well.

I will say that I liked "A Touch of Jen" and found it entertaining, but it felt like it came up short of something great. The characters act deranged at times, and it gets bloody later on, and the satire is witty and sharp, but I regularly found myself wishing for more and the book unfortunately never delivered. The dial is cranked a few hairs away from the right temperature. I still thought it was good up until an Event which takes place three quarters in and which significantly changes the story's trajectory. It makes sense that it did, but I feel like the book lost its lustre for me at that point. The ending makes total sense, it just felt a bit underwhelming. Overall, I think this is a fun book and I do recommend it — I just wish it went further!

One of her roommates has a pet rabbit that roams the living room and sits in Carla's lap like a cat. Carla, unnervingly, doesn't use a baby voice when talking to the rabbit. "Do you want another blueberry?" she says to the rabbit, sounding pissed off.

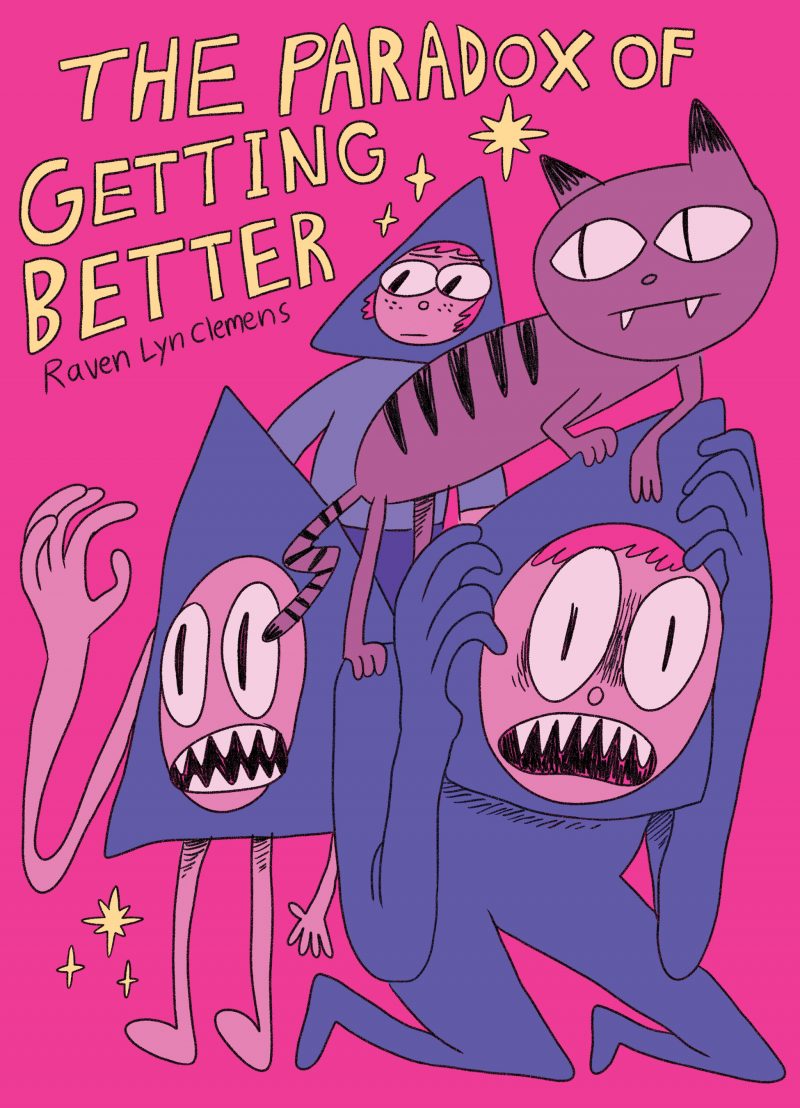

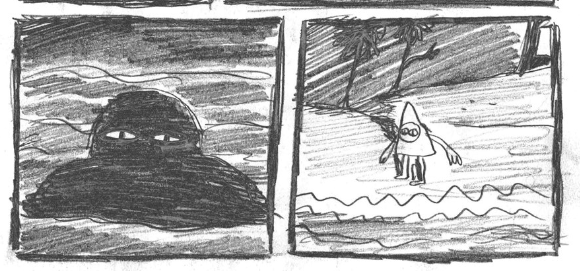

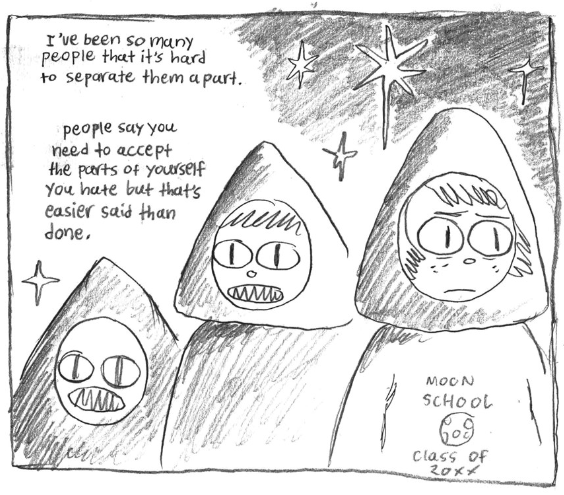

THE PARADOX OF GETTING BETTER

by Raven Lyn Clemens

About

Genre - Comic, mental health autofiction

Reviewed - May 15, 2025

Rating - 5 stars...!

Synopsis

A metaphorical short comic about a young artist and their struggles with mental illness at different points in their life, as told through three vignettes.

My review

I picked this one up because something about the cover intrigued me. I didn't think it would leave much of an impression on me, or even that I would really like it; I rarely truly *like* comics, even if I do like the style of art they're drawn in. Something about the way they're formatted gives me an impression of disjointedness I have difficult getting over, and I don't read them often, anyway, so I feel like I'm very disconnected from them. I want to read more to fix that, which is what tipped me over into reading this.

I did feel some of that aforementioned disjointedness while reading "The Paradox of Getting Better", but I personally found it accompanied the content in a way that came across as intentional. The art is drawn in a very rough pencil sketch style that perfectly matches the tone of the story, too; it gives the whole thing a rough, unfinished feel that lends an almost voyeuristic quality to the story, like you're reading someone's diary. In that same vein, Clemens is skilled at conveying emptiness; the whole world feels like a dream. I particularly enjoyed the strange isolation of the beach from the first part, and how the sky, so ominously black and void, hangs in the background.

Honestly, I did cry while reading this, which was a bit of a shock since I wasn't expecting to at all! The book really knows how to pack an emotional punch, just because of how meditative and sincere it is; I'm not sure if that's an experience *everyone* would go through reading this, and it could just be that I read this at exactly the right time, but I don't think that's it. This book is unique and wonderful and special and clearly so carefully-crafted, and I know it's going to sit with me for a long while. (Also, I really like how the ending complements the beginning so perfectly; I think that reflects on the cyclical message the final chapter gets at, too.) I hate to be *that* person, but you really should read this blind and go along with it on the grounds it establishes; I think you'll be surprised.

THE COIN

by Yasmin Zaher

About

Genre - Psychological fiction, contemporary

Reviewed - May 9, 2025

Rating - 4 stars

Synopsis

A wealthy Palestinian woman unravels spectacularly in New York City. She is building a life for herself; she has impeccable style, meticulous hygiene, a good job, a good apartment — yet her ideal self remains just out of reach. In its pursuit, she becomes increasingly obsessed with cleanliness and purity, struggling all the while to balance her job teaching at a school for underprivileged boys, her various partners, and a scheme to illegally resell Birkin bags.

My review

My uncle was trying to take control of my father's inheritance, but it was impossible, my father was a scientist, he had thought of everything. My uncle showed me the safe and told me the password, which was *America*. I told you already, in my family, America was both the key and the curse.

I'm not exactly sure where or how to categorize this book. I appreciate that ambiguity because it really surprised me! What you get from this book isn't what you go into it expecting; in a lot of ways, it just kind of ropes you along, and you're never able to tell what turn it'll next take. I find that that's quite rare, and treasure the experience whenever I find a book that can deliver it.

"The Coin" defies a lot of convention while remaining very simple at its core, concerned only with one woman and her spectacular denouement. It's absurd and incohesive, almost a stain, in much the same way the narrator can never quite scrub the stain of America off her skin. That layer of filth is important. I would argue the novel focuses primarily on filth. The narrator is fixated on purity, performing increasingly-elaborate rituals meant to 'clean' her: she covers herself in toothpaste, she spends hours exfoliating herself with a hammam loofah, she plucks snakes of dirt from her skin and drowns them in steaming bath water, all of this to a frightfully obsessive degree.

Similarly, the whole novel is covered with a tangible layer of grime, and this comes from a very particular place; above all, the narrator is preoccupied by the presence of a coin in her body, a shekel she swallowed as a child and believes is embedded in an unreachable, dirty square between her shoulder blades. The metaphor is not subtle, but I don't critique the book for that — I feel the bluntness is very tone-appropriate. Something about these rituals in combination with the clinical way the story is told (how grammar is used was very conducive to this — for example, the run-on sentences) and the fact that it's told in short vignettes rather than long chapters (in contrast to the long-winded prose) comes together to give the whole book a really strange and unclean feel even despite its simple minimalism. Many elements of the plot feel flimsy and cheap and mired in pretense — this is, to me, the point.

Technically, Trenchcoat was homeless. It was not exactly a choice, he was dealt a bad hand, and the game is rigged, of course, it favors the better hand and exploits the weak. But at least in appearance, Trenchcoat was wealthy. He wore a perfectly tailored suit everywhere he went, he hung around the expensive neighborhoods, he smiled courteously at old women, he spoke slowly, enunciating all of the letters. His body was lean and strong, his posture the marker of good health.

Trenchcoat believed that one only belongs to a certain class inasmuch as one dresses, speaks, walks, shops, or takes as a certain class does. But his performance was not total. He smiled a lot, he felt comfortable in his own skin, something that made me suspicious from the beginning. Why is it that the rich are uptight and the poor are themselves?

Finally, I wanted to say that this book is really particular. As I alluded previously, the things that happen in it are really weird at times. Not fantastical, never crossing the line into truly absurd, but weird, and operate in strange, karmic cycles. It draws you into itself and its logic. I really enjoyed the role the woman's students play in this book, the weird conjunctions of them and the movement they're inspired to create.

One scene I want to discuss is one in which the woman goes upstate (is that what New Yorkers say?) with her 'partner', a man named Sasha, convinced she needs to get closer to the land to rekindle some vital connection. While there, she gets scared by a deer and realizes she doesn't know the omens of the land she's trying so half-heartedly and ineffectually to root herself in. Later on, she lies down in a stream the same way she would in her tub at home and places leeches on her skin. I found this scene disturbing, sure, but there's something really hypnotizing about the way she describes it that makes you also feel as if you're getting something essential taken out of you in the pursuit of something great. You feel drained and clean. It really stuck with me.

I got close to the ledge and watched the city from above, the brick squares, the moving cars and yellow lines on asphalt. Sasha followed behind me. Don't you want to own a piece of America? I asked. Don't you want to own a piece of the earth? Owning an apartment is delusional, I explained, it's like breathing holy air, or drinking Zamzam water. It's like being buried in a vertical cemetery. After I said that, Sasha looked straight down, there was a police car parked on Hanson, across from the Whole Foods and the Apple store. It was always there. Look around, he answered, I'm the American dream, what more do you expect of life?

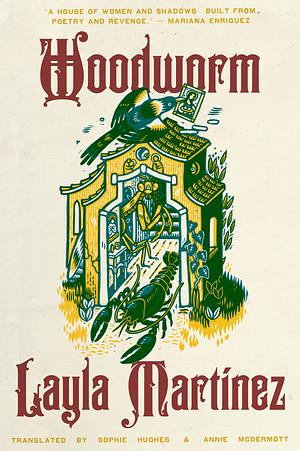

WOODWORM

by Layla Martínez tr. from Spanish by Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott

About

Genre - Gothic

Reviewed - May 3, 2025

Rating - 4 stars

Synopsis

An unnamed grandmother and granddaughter duo live uneasily in a house haunted by saints and angels and shades of the dead. The novel, steeped in class tension, historical wounds, and bitter hatred, opens by revealing that the granddaughter has been accused of a terrible crime - the details of which unfold as the story draws to its abrupt conclusion.

My review

I walked in and the house pounced on me. It’s always the same with this filthy pile of bricks, it leaps on whoever comes through the door and twists their guts till they can’t even breathe.

I *really* liked this book. I listened to half of the audiobook because I was at work, and read the rest later in the week. It has a very unique voice that varies depending on who's narrating, and both narrators seem a bit at-odds with each other's stories - the granddaughter begins by saying she wants to tell us everything as it happened, and in the very next chapter, her grandmother asserts that we have been lied to. The prose is rich and super evocative and suits both the genre, story, and setting perfectly - the book is set in Spain, and the writing carries the same dry and arid atmosphere you'd expect of the Spanish countryside.

Anyone who knows me knows I adore a good haunted house tale, and this one is everything I look for. The house is caught in this very fine tension of being itself a living thing and being a product of what it holds and has beheld, an ambiguity I really appreciated. I'm also a total sucker for books which span across generations, and there's something so satisfying about how "Woodworm" went about it. My only complaint is that I wish it didn't end so abruptly, but that's only because I wish I could have read it for longer. I've seen other people genuinely critique the ending for how quickly it came, but I personally feel it matched the tone of the novel perfectly.

Every review I read of it mentioned how it matches Jackson's "We Have Always Lived in the Castle" (another favourite of mine), and that shows in the resentment the family feels towards the townspeople. They're definitely two very different books, but the similarities are just close enough that it makes for a really fun reading experience. I also want to say that you might like this book if you like the "Mabel" podcast. There are very few similarities by way of the stories, but if you enjoy the show's dense prose and uncertain atmosphere, I think you'll like this book, too!

I shut my eyes and noticed the air in the room stiffen. Then I felt one corner of the bed sink slightly, as if someone had sat down there and the mattress had dipped under their weight. I opened my eyes right away and sat up to look around for my mother, but all I saw was a lock of black hair disappearing under the bed.

When I was little they were always catching me out with those tricks. They’d lure me in with their happy songs and I’d lift the quilt and follow them under the bed, and a few hours later I’d be back in the room with my skin covered in scratches and my clothes all torn, the fear lodged deep down inside me but with no idea why because I couldn’t remember a thing. Now I knew it wasn’t my mother who’d sat on my bed or slipped out of sight beneath it. My mother hadn’t come back to take care of me or watch over me as I slept or to stroke my hair in my dreams.

BRUTES

by Dizz Tate

About

Reviewed - March 22, 2024

Rating - 3.5 stars

Synopsis

In Falls Landing, Florida-a place built of theme parks, swampy lakes, and scorched bougainvillea flowers-something sinister lurks in the deep. A gang of thirteen-year-old girls obsessively orbit around the local preacher's daughter, Sammy. She is mesmerizing, older, and in love with Eddie. But suddenly, Sammy goes missing. Where is she? Watching from a distance, they edge ever closer to discovering a dark secret about their fame-hungry town and the cruel cost of a ticket out. What they uncover will continue to haunt them for the rest of their lives.

My review

"Brutes" was a quick and tilt-a-whirl book. It was honestly sort of addictive - I blasted through it in just a few days during bus rides and 15-minute breaks. It's a strange little saga following a group of girls who refer to them as 'we' and 'us' as they observe their town's unfolding after the disappearance of the local preacher's daughter. The girls are weird and brutish and unconventional as they get bitten by ants and speculate about the monster hiding in the untouchable lake, and the story is interspersed with excerpts from the girls' futures where we find out that sadly the collective of 'we' has been split up into simple first person.

To be loved was just to be watched, or in my case, to imagine you are loved is to imagine you are watched all the time.

I have a few different things to say about this book. I thought the POV choices were really interesting and I loved how the world of sticky childhood disintegrated when hitting the future chapters, the way the dull mundane came to permeate everything. I also loved the setting and the atmosphere! Tate does a great job of enveloping you into the town. On the other hand, this books comes across as trying too hard to imitate a "literary" style of writing in a way that feels insincere and without meaning. Again, the setting is oppressive, almost claustrophobic, which I appreciated, but I feel that maybe the book was trying to hard to present itself as having a certain vibe than actually going through with putting any substance behind that appearance.

Overall I did like this book, but I see what it could have been and consider what went wrong; it's too muddled, too obsessed with appearances. This book is enjoyable but, once you finish reading it, you realize that it is in fact a bit shallow. Still, I recommend it - it's a fun read!

They called us brutes when we got tired of being called brutes and collected dead wasps with their stingers still in, slipped them into their work Crocs, the coin section of their purses.

'Brutes! How can you girls be such brutes!'

THE DOLLS

by Ursula Scavenius tr. from Danish by Jennifer Russell

About

Reviewed - March 19, 2024

Rating - 4 stars

Synopsis

In the four stories that make up The Dolls, characters are plagued by unexplained illnesses and oblique, human-made disasters and environmental losses. A big sister descends into the family basement. Another sister refuses her younger brother. A third sister with memory loss is on the run and offered shelter by Notpla, a man both an ally and an enemy. A fourth set of siblings travel to Hungary with their late mother in a coffin.

My review

I picked up "The Dolls" after watching a video by Dakota Warren titled strange books for strange people. It's a short story collection that is truly and unequivocally *bizarre*. The stories all take place in a strange world that is perhaps our own, in time periods that feel out of time. I found Scavenius to be a master of juggling reality with unreality, so that the final result is something slippery and difficult to grasp.

Most of all I feel these stories tackle the question of identity and somehow, sisterhood. Each story centers on a sister; in the first, a sister, in defiance of the 'woman locked in the attic' trope, hides herself away in the cellar of her own volition. In the second, a sister offers shelter and betrayal in equal measure; in the third, a sister toes the line between safety and danger. In the fourth, a sister tries desperately to uphold the legacy of her mother. This sisterhood is not much commented on, but it is still front and center to each story simply by virtue of being an explicit identity.

Scavenius' stories do more than just defy trope and convention, however; they also forgo it altogether. It is difficult to keep your place in the stories, that's how nonsensical they are in a way that pays sincere homage to the very nature of personal identity.

I really enjoyed this book. I thought it was strange and weird and insightful, and I sincerely recommend it to anyone looking for a short but offputting read.

I'll tell the story, even if no one is listening: A shadow trailed after me the other day. It appeared in glimpses, one moment to my right, the next to my left. I kept on nervously turning around to look for it as I walked. Suddenly, it was gone. It must have been someone who lost their way, I thought.

CONVENIENCE STORE WOMAN

by Sayaka Murata tr. from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori

About

Reviewed - January 20, 2024

Rating - 3 stars

Synopsis

Keiko is 36 years old and has worked in a convenience store all her life. She's never had a boyfriend, or been in love, or even thought about any other job. The store makes her happy, and yet, the people around her are so insistent on her changing that she begins to wonder what, exactly, is so wrong with her way of life that others cannot stand it.

My review

This book was quick and charming. As a narrator, I found Keiko endearing, but I've always had a problem with most translated books where the translation feels a bit stiff, and I imagine that this is not the case in the native language version of the book. That's why I usually prefer reading the original copy, but since I don't speak Japanese even a bit, I relegated myself to the audiobook version. That stiffness is maybe part of why I rated this book lower than I would have.

I thought this book didn't have much to say, but what it did have, it said very eloquently. It dedicated itself to exploring why Keiko wants to work in a convenience store for the rest of her life. The book gives her the opportunity to switch careers, but it's obvious that it's not what she wants to do, and I appreciated the fact that Murata made it clear that while society might encourage and want Keiko to act a certain way, that way of acting is not what makes her happy.

Unless I'm cured, normal people will expurgate me.

I read a few reviews in preparation for writing my own, and I found a lot of them had a frustration as to Keiko's perceived lack of character development. She begins and ends the book in exactly the same position as the convenience store woman. I disagree. I think, for the length of the book, the book demonstrates a perfect development of Keiko, not in physical state, but mental. She begins the book puzzled as to if she should work at the store or not, preoccupied with society's expectations of her. She wants to prove herself cured, and is ready to bow to people's expectations of her to prevent ostracization. At the end of the book, she is able to accept that the store is what makes her happy and that she doesn't particularly care what society, presenting itself in the form of her incel coworker, thinks about her.

Again, I think Keiko was a charming protagonist, but the fact that the book didn't afford much more space to really getting into the intricacies of its thesis paired with the stiff feeling of the translation diminished its impact on me. Still, I found it entertaining and enjoyed Keiko's dry wit and the societal commentary.

OUR WIVES UNDER THE SEA

by Julia Armfield

About

Reviewed - January 18, 2024

Rating - 4 stars

Synopsis

Miri can feel Leah slipping from her grasp. When her wife returns after a catastrophic deep sea mission, Miri is thrilled to think she might have her back, but increasingly it becomes clearer and clearer that something happened to Leah in the dark and the cold, and that perhaps the Leah that now haunts the flat they once shared is no longer the Leah that was.

My review

I went into this book not expecting much. I’d heard about it through a video on Instagram, I think, which is not always the best place to get book reviews. I went into it expecting something silly and shallow (get it?), and definitely a lot more horror-focused than it ended up being. However, “Our Wives Under the Sea” beat every expectation by a mile, and quickly became a contender for one of my favourite books of 2024, so early in the year.

OWUtS presents a slow and ambling mediation on grief and loss, and the ways in which people can be both there and absent all at once. The story of Miri and Leah’s quiet present is spliced with anecdotes of their love story, and the alternation between the loud joy of their first dates to Miri’s bitterness towards the woman she loves is jarring and good to chew on.

Standing at the place where one fades into the other, I have always been sure that I feel it: the sudden confusion. The air drawing taut between one stage and another. Looking out across the water and feeling my feet connected to something more solid than the plunging uncertainty beyond, I have always felt weighted, literal, a tangible creature connected to the earth.

I loved the prose style Armfield chose to write this book in, and I loved, too, the alternation between Miri and Leah’s chapters, below and above water. This book leaves all your questions unanswered in a way that is deeply satisfying - this is not a book about horror, or strange marine institutions, or whatever lurks there in the deep where no one goes. It is a story about love and loss, and the strange, aching ways that grief yawns in the chest when nothing tangible has been lost.

DEAR LAURA

by Gemma Amor

About

Genre - Horror

Reviewed - January 17, 2024

Rating - 1 star

Synopsis

Every year on her birthday after the disappearance of her best friend Bobby, Laura gets a letter from a stranger claiming to know his whereabouts. This stranger offers that information to her, piece by piece, in exchange for disturbing personal effects. This relationship goes on for years, time passes, and Bobby remains unfound - and then, her mysterious penpal suddenly disappears, leaving Laura thoroughly changed.

My review

Where even to begin with this book? It was dull, boring, uneventful, trite, any adjective you can think of, this travesty of a book was. It doesn't even deserve that title, it was just that dull. I've seen multiple people endorsing this book, recommending it as something thrilling and horrifying, something that you'd keep thinking about for weeks after reading it. It's very short - the audiobook was just an hour or two in length. I went into this with pretty high expectations, then, bearing the stellar reviews in mind.

The problem with this book isn't fully that it's boring, because that's just my opinion of it. Rather, the problem is that the book is too obsessed with itself in a way that is disarming to the reader, and that disarmament leads to its flaws being noticeable front and center. The primary antagonist of this book is, surprise surprise, Laura's penpal, who refers to himself with the moniker X. He's a run-of-the-mill predator and killer, every cliche movie villain rolled into one nauseating stereotype. Amor's X brings absolutely nothing new to the table, but nor does he subvert or play with any of the previous tropes established. That's okay. That's alright. But, and this is crucial: Amor is not equipped to handle the breadth of the monster she has created. This is where many films and books featuring non-fantastical villains fall flat for me: Too grounded in reality, and wholly incapable of sustaining their own mystery.

Amor paints X as a villain who is able to twist Laura up into knots, grooming her from a very young age to be pliant with his demands. Nothing about her relationship to him *doesn't* make sense, as sickening as it is. But all of this stickiness, all of this wrong feeling, deflates miserably towards the middle of this story where there are significant issues with the pacing as Laura rushes through adulthood, and that, combined with the increasingly (unintentionally) pathetic air of her tormentor leads the reader waiting for the book to end so they can get on with their day.

The ending had the same issue: Not surprising, not interesting. It's visible from a mile off, and not in a way that feels satisfying. All in all, I would not recommend "Dear Laura" to anyone who's not looking to waste a few hours of their life. It's boring, it's trite, it's a nothing kind of book.

PROCEDURES FOR UNDERGROUND

by Margaret Atwood

About

Genre - Poetry

Reviewed - January 17, 2025

Rating - 3.5 stars

Synopsis

"Procedures for Underground" is a book of poetry written by Canadian author Maragret Atwood and published in 1970. It is composed of forty-four poems.

My review

I started reading Atwood in 2023, and this is the second volume of poetry by her that I've read. The first, "Power Politics", quickly found its way onto my list of favourite books ever and of all time, so I was super excited to read this one, too. However, I found this volume to be a lot more divisive than the other book. I found some of the poems quite lackluster, even though Atwood writes them all with the usual competent and lyrical style. Even though some poems were bad, the ones I enjoyed, I enjoyed immensely! I highly recommend "Game After Supper" and "Delayed Message".

The titular underground was understood by me to be a nebulous kind of space in which anything and everything is possible through mediation and self reflection. It's a place where metamorphosis happens, where sudden bright ideas are had, or the inverse; where shocking truths are revealed. This extraphysical space is, to Margaret Atwood, the titular *underground*.

I really enjoyed the books recurring motifs of lakes and water. The whole collection has a kind of watery, earthy feel about it that Atwood maintains wonderfully across poems and sections. I really admire writers and poets who are able to consistently maintain that kind of dense atmosphere. Overall, while I didn't like this volume as much as "Power Politics", I think that "Procedures for Underground" is a solid and overall enjoyable read for a rainy, moody afternoon.

Procedures for Underground

(Northwest Coast)

The country beneath

the earth has a green sun

and the rivers flow backwards;

the trees and rocks are the same

as they are here, but shifted.

Those who live there are always hungry;

from them you can learn

wisdom and great power,

if you can descent and return safely.

You must look for tunnels, animal

burrows or the cave in the sea

guarded by the stone man;

when you are down you will find

those who were once your friends

but they will by changed and dangerous

Resist them, be careful

never to eat their food.

Afterwards, if you live, you will be able

to see them when they prowl as winds,

as thin sounds in our village. You will

tell us their names, what they want, who

has made them angry by forgetting them.

For this gift, as for all gifts, you must

suffer: those from the underland

will be always with you, whispering their

complaints, beckoning you

back down; while among us here

you will walk wrapped in an invisible

cloak. Few will seek your help

with love, none without fear.