hypothesis: whales are wiser in water than out

I found the whale where it always was, at the edge of the sea.

The whale was dead, but it could still speak, and think, and dream. I once told the whale that I had watched a video that said dead whales exploded because of a gas buildup within their bodies, and if it was dead then why hadn’t it exploded yet? In answer it told me that only happened to beached whales and anyway, if I was going to doubt the authenticity of its dying or not dying, we shouldn’t talk anymore. I hadn’t wanted that so I’d apologized.

I didn’t know why no one else talked to the whale. It wasn’t like it was hidden because the waterside was right up next to the road, and there was a neat row of white-walled shops across from it. People took time to shake their fists at the thieving seagulls that wheeled in the air and to coo at the small dogs tourists trotted around on short leashes, so why not the whale? The whale was very wise. It had lived a long life, and it had the biggest brain of any mammal alive today. Whenever I needed advice or answers, I asked the whale, like when I asked it why my closest friend Laura-Jane Grace only let people call her by her full name, first and last.

“Simply put, she has three first names,” it had told me after a moment of ponderation, “and she feels as though only Laura-Jane, or Laura Grace, or Jane Grace, would be like picking one name over the other. You should never pick favourites out of names for this drains them of their potency, and when the fish swim into your head at night they will have nothing to draw their power from and will simply die right there, in your mind, and you will stink like rotten fish for weeks and weeks after.”

I sometimes found the whale so exquisitely wise that it blew my mind.

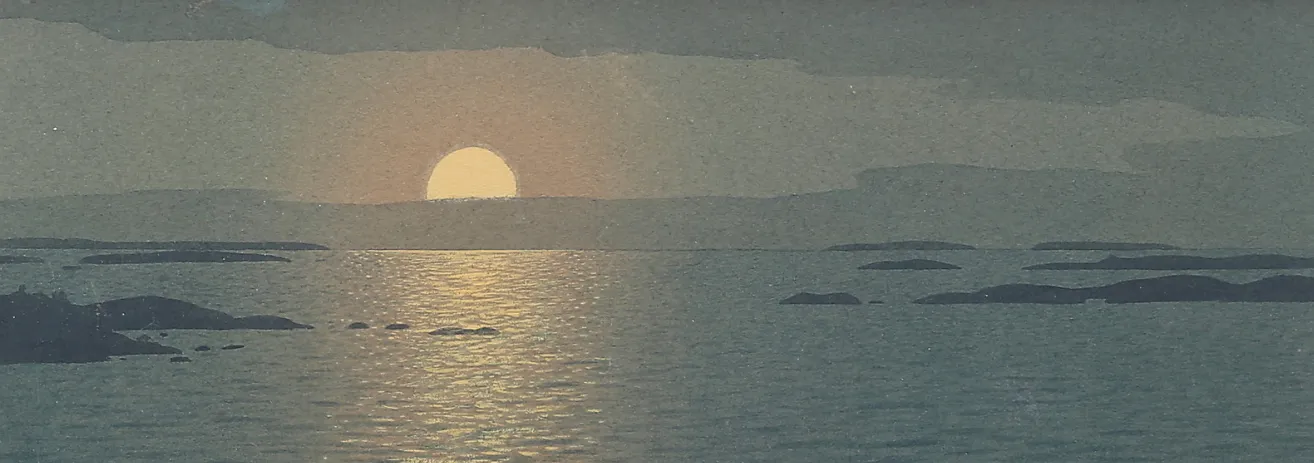

“Hello,” I said to it today, drawing up short. The sea had been tired recently. It was trying to put up some sort of a fight, but it couldn’t quite get there — the waves were breaking at the cement crash barriers that demarcated the edge of the land, and the water was a dark and moody reflection of the overcast sky. They’d had a falling out recently, but maybe one of them would take the other out for dinner and then the sky would be sunny and bright and the sea would be playful and clear.

When it heard me approaching, the whale turned slightly so it could look at me all the better. Sometimes, it dawned on me just how huge it was. It had let me touch its side not so long ago and it had been soft, not rough and leathery like I’d been expecting. I could feel the lumps and divots where its skin creased and wrinkled up and folded. Its misty eyes looked far away today, meaning it was caught up in reminiscences of the deep blue.

The whale told me that it liked its new home where it could observe human beings like we did its kind from our boats, but it said that the loss it felt for its lively haunts was worse than the joy. It had told me about salt spray and vast expanses of nothing, nothing above the water except for the clarion call of the wind. It told me much of this years ago, when I was smaller and less sensitive, and I’d asked it if it had ever battled a giant squid; in retrospect, I understood how this must have been disappointing. I felt ashamed whenever I remembered. How embarrassing! It had taken all the years in between to convince it to share those stories again.

“Hello, sea sponge,” the whale said to me. “How are we?”

I dropped my bag on the crabgrass, nudging it with my foot so it leaned against the crash barrier. I sat and swung my feet over the water. I knew that I wasn’t technically supposed to do that. Two days shy of seven years ago a woman killed herself, or was killed, or accidentally fell into the sea one night. They found her body washed up a few towns down the coastline. The city had had to invest in a bunch of safety measures and PSAs, and the fire department had visited both elementary schools and both high schools to give us all a talk about safety at sea. I’d been in the second grade at the time, and we’d all gotten stickers shaped like life jackets afterward. I still had mine, pressed safely behind my closet door where I put all of my stickers so that Mopey-Cat, who was scared of my closet, wouldn’t scratch at them.

“I’m okay. A little tired. How was your night?”

The whale was silent for a few moments so that all I could hear was the quiet lapping of the waves. I studied the frothy foam intently, like the coffees Dad said were overpriced but kept buying anyway, and the seaweed and driftwood, which were dried out and sold at the shops Dad said were also overpriced, and silly and meant to rob tourists out of their hard-earned dollars.

“It was restful,” the whale finally said in its slow voice. I appreciated how the whale took its time to say everything, because that meant that there was a weight behind its words that I thought wasn’t always there to mine. “The seagulls came during the early hours. They sat where you are sitting now,” and it blew a bit of mist out of its spiracle, “and asked me to serve justice.”

I perked up. “Were you good at serving justice? Did you send anyone to jail? Did you give anyone the death penalty?”

“No one was thrown in any jails or given any penalties, deathly or otherwise. You should not jump to these conclusions,” it admonished. “They came to me on the air … First, they were squabbling as they flew above me. I could hear them arguing with one another from all the way down here, and you know how my hearing has gone, what with the dying and all.”

I nodded emphatically. The whale had told me about this before. Its hearing was one of the few things it liked complaining about, unlike me. I could complain about anything.

“So I called up to them, I did,” it continued. It blinked, slowly. “I said, Hail! Why do you quarrel, gentlemen? and at first they were upset with me for interrupting, they called back down that I ought to mind my own business. I thought that would be the end of it, because they flew off after that and it became quite silent.”

“But then?”

“They must have wheeled back around as I began to hear their voices again, though what for? As it turned out, it was for me! Can you imagine?”

I could imagine it very clearly. The whale was very wise. It made sense the seagulls, who were all very shallow and preoccupied with fighting amongst one another, would be able to see this.

“They said to me they did, ‘We were rude to you just now!’

“‘Of course you were,’ I replied, ‘but I did not let it affect me very much.’

“‘We were just arguing,’ and I ought to add that it was their leader who was saying all of this, the great Lady Salami Sandwich, ‘over a little something that happened to us this evening. Hotdog With Fries,’ — here, she had to flap her wings about to coax Hotdog With Fries out of the gaggle — ‘and Extra Large Coca-Cola had a spat. They had a spat over spoils.’ The matter was that they’d attacked the same person at once and that person had dropped their fries. She carried on, ‘Now, Hotdog With Fries says he deserves more because he’s predestined because of his name, right, and Extra Large Coca-Cola says he deserves more because he’s the one that actually dive-bombed the guy. Thoughts?’

“Here, they all started to jostle in order to get a better look at me. I found myself faced with a dilemma. While I agreed that Extra Large Coca-Cola had done most of the hard work, who was I to disagree with preordination? Who was I to challenge what was nominally established already by the powers of fate?”

“Who did you pick?” I asked. I had not known that seagulls could have such complex social dynamics. The topic had never really come up between us. I pulled my knees up so that I could rest my chin on them.

“Who would you have picked?”

This gave me pause. The whale often liked asking me these questions of philosophy and critical thinking and whatnot, and it was fun, but a lot to think about on the way back from a Mathletes session. A lot of stuff happened in Mathletes that wasn’t math, so I felt like I really got to touch all of my bases every time we had a session. This time, there’d been an intense discussion about whether or not Arnie was allowed to name his cat after a Greek philosopher (the consensus was: Yes, if the philosopher was established as having cat-like traits).

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “I think Extra Large Coca Cola.”

The whale considered this. “Interesting.”

“Was that the right answer?”

The whale turned a critical eye on me. “There is no right and wrong answer to questions regarding the Universe.” I could tell instinctively that the universe came with a capital U, all the records smashed, cosmic expansion, flat-out.

“Who did you pick, then?”

“I’ll tell you what, I do think I’ve forgotten.”

I huffed out an annoyed breath, but I couldn’t stay bothered for too long. We stayed still for a few moments. The whale just floated, sometimes with its eyes closed and sometimes not; I sat, mostly with my eyes open, because I didn’t want to fall forwards into the water. I had a biology test tomorrow.

The whale told me that I worried too much. It said that I focused too much on things that didn’t really matter. Sometimes, when I had, for example, had a big fight with Laura-Jane Grace, or not done very well on an English reading response, or skinned my knee trying to do a trick the older kids would find cool at the skatepark, some of those times the whale would listen to me crying and I could tell, I could just tell that it wished it could reach a massive pectoral fin out of the water and make me feel better; sometimes when these things happened, it sat quietly and listened to me as I told it what had happened.

It bothered me that the whale thought I was bothered. I didn’t like thinking of myself as a very bothered person. Mostly I just tried to do the things in my life that needed doing with as little fuss as possible, and it upset me when those things wouldn’t cooperate.

“I have a biology test tomorrow,” I said. I couldn’t tell how much time had passed between now and when it had said it had forgotten the verdict. Oftentimes staying with the whale made me lose track of time.

“What on?”

“Cell structure.” I picked at the dirt caked in the grooves of my sneaker. “Cell wall and membrane and nuclei and stuff like that.” I thought I would probably do okay on that test. I had studied, but I also always did well at biology. I liked learning about whatever things ticked beneath my own jaw. The dirt was packed in really tight so I had to angle my nail to dig it out. I wanted to pitch my hypothesis to it tonight. The hypothesis had been scribbled onto a legal pad that was crumpled up in my bag somewhere. The page read, in order:

Pros: The whale won’t be lonely and I won’t be lonely. I’ll learn a lot of new stuff.

Cons: I might annoy the whale eventually, or vice versa. Dad might be worried.

I took a deep breath and I asked: “Do you want me to join you?”

“Sorry?”

“In the water. Do you wish I would stay with you all the time?” Now that I had actually broached the subject, I felt distinctly like I had fumbled the bag.

The whale gave this due thought. I appreciated the whale because it thought about the things that I said. Dad also thought about the things I said, but not any of the big things. If I said I wanted spinach instead of okra for dinner, he would think about that; if I said I wished he thought about what I said more, he would not think about that. “I don’t think I do.”

My stomach sank. “Because you don’t like me?”

“Well, I never said that, now did I,” the whale said severely.

“But don’t you get lonely all on your own?”

“I have the seagulls,” it answered in its strange, melodic voice. “I have the sun and stars wheeling above me … I have the small fish and the barnacles beside me … I have your occasional company … what else is there to want?”

I shrugged, unzipping my back and pulling out the paper. I read aloud from the back: “When Laura-Jane Grace is absent from school, I wish she was there with me. When Dad has to work late, I wish he was home. When I am all by myself, I start to feel lonely and sad and I wish that I had someone to spend the time with. Don’t you feel that way when you remember you used to have friends and family that were more your size?” I felt that when I had finished saying this, I had been rude or maybe insensitive. Sometimes, I said things that were rude or insensitive without really realizing it, and then I had to figure out what I had said wrong so I could apologize. The whale didn’t get upset with me, though when it next spoke, it sounded a bit more unhappy than it had before.

“Of course I did. But you know, after a while, it came time for me to be on my own. The being alone isn’t the issue; I was alone for great huge swathes of time when I was alive, just me and the water for as far as I could see. Sometimes there would be other whales, and we would stop and talk, and sometimes there would be great schools of shining fish, or if I came too close to shore, your lot in your metal contraptions, and once, just the once, a great and massive squid with an eye the length of a trout. Can you imagine that?”

I imagined it long and hard, but I got distracted midway through the imaginings and my thoughts turned instead to the changing seasons. Soon it would be cold enough that I would have to leave my sweater-windbreaker combo and instead shuck on a real jacket, my purple one that had the hole in the left pocket I kept accidentally letting coins drop into. I thought about tearing open the seams of the coat and letting a thousand dollars in dimes fall onto my feet. I thought about how I’d tried making a well to wish into in the yard of our house last summer, digging with a plastic beach shovel until it got too difficult and then filling it with water from the hose, dropping a few pennies into the dark muck before losing all interest in the endeavor. I used to bury things in the yard a lot. When I got tired of my dolls, I buried them all by the shed because I couldn’t stand to see them thrown out; when I lost my milk teeth, I buried them in the roots of our solitary tree. Maybe those teeth would grow up and out of the ground one day into strange and nervous little plants that would hang incisors like lily-of-the-valley. I wondered if the same would happen to me when I died and all of my adult teeth stayed firm-set in my jaw. They couldn’t grow, because they would hit the wood of my coffin and wilt in my mouth. This made me very sad. I turned my eyes to the whale, who did not have teeth but rather something like thick bristles that I found a little disgusting to look at. The whale was dead, and here it was.

What I was sure of was that it was the water keeping it suspended in its state of death or rather, undeath. When humans were buried they were put under the ground, in a box of wood. There was no air down there — but humans weren’t birds, and nor were they earthworms, which begged the question of where, exactly, a human could be put in order to stay alive. Certainly not water. What then?

“I wouldn’t know,” the whale informed me matter-of-factly. I didn’t know how it could sometimes read my thoughts. “I did not ask for this afterlife. One moment I was, and the next I was not. I think I was different in life.”

I blinked. I was still holding the paper, so I folded it up and jammed it into the crack between the concrete of the crash barrier and the grassy ground. The sun had started to dip lower in the sky. Dad only got worried if it got dark and I hadn’t come home yet, so I knew I had a few more minutes before I had to hurry up. “How?”

Whales couldn’t shrug, but it moved its tail in a way I thought was supposed to convey the same feeling. “I think that I was more impatient then. I remember once that I found myself drifting along, barely older than a calf if memory serves right. I met another whale who was much older than I. If I had been even a few seasons older I might have stopped and said hello; but I did not stop on this occasion. I find myself lamenting these things more and more as I carry on unliving. I do not think this is natural, in truth; but what can be done to deter it? So fate has said it shall be and so it is.

“Shortly after I did not meet that whale, I found myself by the coast. Not close to it, but closer than I had previously dared. I spent the night there, not doing much of anything. There was a thick fog roiling across the land and water, a dense mass like a giant had gotten cold and was breathing into its hands. Through the fog I heard a music. It was at first quite faint, but as I strained my ears to listen, it grew progressively louder. It was a great deal of song but with no words, like the chiming of a great many bells all on top of one another. I find our kind’s music to be somewhat mournful, but this song was much more so and as it was sung, I found in my heart a sadness for all beautiful things crafted by the cradle of the waters and I wished to go see them all before time and weather swept them where even I, with my shape and my territory, could not follow. I wanted very badly to see everything and to keep it all in my head, but in the end I reasoned that because there was no way I could see all of it, I was better off seeing none.”

The last rays of the sunset peaked shyly out from behind the horizon. My chin was digging into my knees, but I could not tear my eyes away from the whale’s story. I thought suddenly of Dad at home alone, one ear pressed to his phone, the other drizzling olive oil over asparagus. The lights would be on, spilling honey-butter over his shoulders, and the curtain would be drawn above the sink, a small window into the blue night all the better to see my coming up the stone path, ankles getting wet from sprinkler-dew as I cut across the lawn.

“That was a stupid decision,” the whale continued hypnotically, voice like a clock, set for an unreachable destination, quiet but persistent. “I know this now, when nothing can be done to change it. I fear that once my mind was sharp but stupid, and my speed was great but misguided. I was as a fine arrow to a poorly-strung bow, or an ache in the razor-tooth of a shark. You can never have all of the discretions of time and wisdom at once, I have learned … life passes one by at great speeds. As I grew, I returned often to that shore in pursuit of that same music. I thought I must have gone mad that night, or fallen victim to the fog’s tricks, because I never did hear it again. I set a watch there, hidden in shadows and kept so still that I thought I might not be able to see my own self were I to look at myself from a meter outside of my body. I remained there for seven days and seven nights. Many fish swam up to me in the daytime to ask me why I had positioned myself there, but I found myself in a latent trance, unable to speak or to think of anything but the faintest recollection of bell-song.”

“Did you ever hear it?” I asked. It was very cold. The wind was blowing eerily across the water and through the narrow alleyways behind me, a gentle sound like a person walking, walking, walking to a place just next to me. Coupled with the restless rest of the water, I felt distinctly as though I was not alone in my vigil. I shivered in my hoodie.

The whale closed its eyes for a long moment. I feared it had gone to sleep, and began to move to stand; my foot had fallen asleep long ago. “When I was much older,” it said suddenly, “and I had all but given up on hearing the music again, I swam back. I do not know what possessed me to, for I had largely lost my conviction. I was sure and certain that it had been a message from the Universe. This was my scientific process, as you documented yours. Do you still wish to join me?”

I looked out over the sea, at its gaping maw. The sea was a beast that could and would swallow me whole. I imagined holding onto the whale as the water swelled up to take us both over whole in stormy weather. I imagined catching fish raw and eating them at mealtimes. I thought about lying on the whale’s back every night, blinking up at the stars and tracing faces in them, coining new constellations with which I could track the heavens. Then I wondered if that would be counted as rubbing my aliveness in the whale’s face. “I don’t think so. The point was never being in the water. It was just making you happier.”

The whale trained an eye on me. “When I was much older and I had all but given up on hearing that music again, I swam back.”

“You said that already.”

“I went under the cover of darkness, and there I found a vessel haunting my own haunt. There were floodlights pointed down into the water, but as I stayed in place trying to assess the situation, they all shut. My eyes had not yet adjusted to the darkness when I heard the vessel further approaching. Let me tell you something now about the sky. No, rather about the stars … .” It trailed off. “You asked me before if I heard the music again; I will say I never did. I heard the vessel approaching, but I was so very tired. And I will also say that the next thing I remember is you throwing a pebble at my head to see if I’d explode.”

“Oh.” I bit my lip. “So you never got to see, either.”

“What?”

“All the beautiful things,” I said, “all the pretty coral and the rock formations and the deep trenches and every living thing in the sea. You didn’t even get to see any of it, did you?”

The whale, shaken from its stupor, said: “What can be made of a single regret but to revisit it time and time again? What can be made of the driftwood and the kelp-tangles as they drift up on the shore? What can be made of the sun falling quietly to sleep every night as her sister-moon keeps a watchful eye on all good creatures? They are all gone for they know their peril and they know what comes of clinging too strongly to what is best left untouched; they know that there is an order to the passage of time that ought not be quarreled with. And tell me, my little bird, are you not missed? Is there not a home waiting for you in the bleakness of the night? Go! Go and let me not hear you speaking of joining me in the water again.”

And all I could say in response was, “Good night.”

When I came back two days later, the whale was gone. I didn’t have my jacket, but I had a quarter, so I flipped it into the water for its trouble. I looked out across the sea again, on and on as far as I could see. What could be made of a single regret? I vowed to bring the subject up at next week’s Mathletes.

Behind me, Dad honked the car horn, twice and in rapid succession. I appreciated him taking time out of his day to drive us to the graveyard. All good creatures slept under the watchful eye of the sister-moon, I told myself. All good creatures, and in the past when people died, a little bell and rope system was linked from the casket to above-ground, so that if a living person were to be interred, they could draw attention to their plot. I had insisted on one of these. Maybe I was ready. I had kept the whale company, and that had to count for something. I thought very hard about throwing the bouquet in my hands into the water after the quarter, and I thought about jumping in myself, doing a lap around the coast, the continent, the world, seeing all those beautiful things that it had been too scared or too sad to see, all of the coral and rocks and trenches, every living thing that I could possibly level an eye to. But the story went like this: Seven years ago a woman had fallen into the water and she’d not come back out with all her parts right. For one, no unbroken hands with which to ring the bell.

Dad honked the horn again, and the sound was loud enough that I was scared we might get a noise complaint.

I said: “Coming!”

I turned my back to the water.